With ongoing conflict in Western Asia and a presidential election in Indonesia, the media headlines for prominent global Islamic regions have been fairly predictable over the last month. Many in the Western world are likely to have missed not only the holy month of Ramadan, in which Muslims abstain from eating, drinking, smoking and sex during daylight hours, but also the three-day Eid al-Fitr festival that marks the anniversary of the Quran being revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. Eid al-Fitr, also referred to by the shortened “Eid” or “Eid Mubarak,” occurs at the commencement of Shawwal, the tenth month of the Islamic lunar calendar, and signifies the end of Ramadan.

Watching the night sky

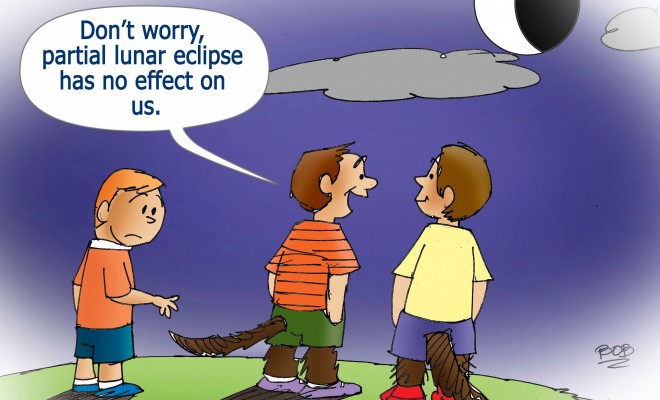

The Eid celebration, which ends today, can only begin after the new crescent moon appears—for some Muslims, this means actually sighting the moon each year. While the occasion may seem straightforward, the Rooyat-e-Hilal committee was founded in 1999 in North America by followers who believe that the Quran requires a sighting conducted with the naked eye.

Both the Fiqh Council of North America (FCNA) and the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) maintain the position that astronomical calculation is a valid Shar’i method for determining the start of the month of Shawwal. However, for Muslims such as Sunni cleric Mufti Qamar ul Hasan, who is based in Houston, Texas, U.S., the use of a preset calendar is insufficient. Hasan explained to a journalist this year, while waiting for the first crescent sighting in his home city: “There was no one body that made sure the decisions were consistent.” The “decisions” he refers to are the differing opinions from across the world about when the new crescent moon actually appears.

On Sunday evening this week, Rooyat-e-Hilal committee members, in locations such as Houston, New York, Toronto, Florida and San Francisco, used telescopes to catch the first sign of a lunar sliver. For an ancient religious practice, modern technology was vital as, in addition to the telescopes, the members stayed in contact by cell phone, so that sightings could be reported in real time, and engaged in a conference-call discussion. Hasan, the committee’s chairman, was responsible for finalizing the official start time of Eid, which was declared on the committee’s website after the reported sightings were taken into account. This year, the first reports came from Chile and then New York, the American location with the highest number of committee members.

A seasonal occasion like any other

Akin to the sales that accompany the Christian celebrations of Easter and Christmas, marketers increasingly perceive Islamic observances as retail opportunities. While the vast majority of businesses in the U.S. have been hesitant to venture into Muslim marketing territory, due mainly to the domestic political climate fueled by the media, the inertia did not discourage the Atlantic magazine’s website from questioning “Why Are There So Few Ramadan Marketing Campaigns?” on the first day of Eid this year. In the article, Sabiha Ansari, cofounder of a U.S.-based Muslim marketing focus group, explains: “The market is growing and it makes good business sense for companies to start [marketing toward Muslim consumers] now.” In a nation where the Muslim population is expected to rise to 6.2 million in 2030, Ansari’s words are likely to resonate with businesses that are looking to expand over the next two decades.

Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom the results have already proven Ansari’s “good business sense” and have attracted established finance publications like the Wall Street Journal. According to the WSJ this year, Ramadan is second only to Christmas in a country with a Muslim population of around 3 million that is expected to nearly double by 2030. Additionally, upmarket U.K. department store Harrods provides Arabic-speaking customer service representatives, as well as cultural training for its employees. In terms of figures, U.K. Tesco ran its first Ramadan promotional campaign in 2012 and reaped US$51 million revenue from 315 stores; unsurprisingly, the campaign was repeated the following year.

Intercultural awareness

Of particular importance to both businesses and the wider community is an awareness of both Islam and the diversity among its followers that can be attained through recognizing Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr. For Australian non-Muslim author Christopher Kremmer, who wrote The Carpet Wars: A Journey Across the Islamic Heartlands, participating in Ramadan for the first time this year was more about the soul, whereby “the suffering of the unlucky reminds the fortunate to be grateful.” In the United States, Ansari speaks of a new generation of American Muslims that is different from the immigrants of the 1960s and ‘70s, and “want to join their faith with being an American.”

Shelina Janmohamed, vice president of an Islamic marketing consultancy agency, asserts that many younger American Muslims are most interested in non-traditional cuisine that suits their Americanized identities. American company owner Adnan Durrani, whose “Saffron Road” halal food company ran its first Ramadan marketing campaign in 2011, also relays experiences with young Muslims who are enthused by products that are outside of their parents’ typical tastes.

The futurists

Durrani has used the term “futurist” to describe the young Muslim customers that he has been serving, as he believes they are laying the foundations for a new generation that makes purchases based on a company’s practices, rather than religious tenets. And now, with the emergence of Islamic banking institutions in the U.S., which adhere to the Muslim belief that lenders shall not collect interest on loans, the unpredictable future of the market is further transformed.

Facebook

Twitter

Pinterest

Google+

LinkedIn

Email